Can computers be creative?

The EU-funded ‘What-if Machine’ (WHIM) project not only generates fictional storylines but also judges their potential usefulness and appeal. It represents a major advance in the field of computational creativity

Science rarely looks at the whimsical, but that is changing as a result of the aptly named WHIM project. The ambitious project is building a software system able to invent and evaluate fictional ideas.

‘WHIM is an antidote to mainstream artificial intelligence which is obsessed with reality,’ says Simon Colton, project coordinator and professor in computational creativity at Goldsmiths College, University of London. ‘We’re among the first to apply artificial intelligence to fiction.’

World’s first fictional ideation machine

The project acronym stands for the What-If Machine. It is also the name of the world’s first fictional ‘ideation’ (creative process of generating, developing, and communicating new ideas) software, developed within the project. The software generates fictional mini-narratives or storylines, using natural language processing techniques and a database of facts mined from the web (as a repository of ‘true’ facts). The software then inverts or twists the facts to create ‘what-ifs’. The result is often incongruous, ‘What if there was a woman who woke up in an alley as a cat, but could still ride a bicycle?’

Can computers judge creativity?

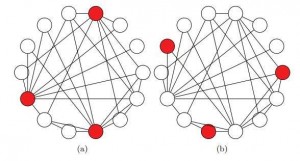

WHIM is more than just an idea-generating machine. The software also seeks to assess the potential for use or quality of the ideas generated. Since the ideas generated are ultimately destined for human consumption, direct human input was asked for in crowd sourcing experiments. For example, WHIM researchers asked people whether they thought the ‘what-ifs’ were novel and had good narrative potential, and also asked them to leave general feedback. Through machine learning techniques, devised by researchers at the Jozef Stefan Institute in Ljubljana, the system gradually gains a more refined understanding of people’s preferences.

‘One may argue that fiction is subjective, but there are patterns,’ says Professor Colton. ‘If 99% of people think a comedian is funny, then we could say that comedian is funny, at least in the perception of most people.’

Just the beginning

Generating fictional mini-narratives is just one aspect of the project. Researchers at the Universidad Complutense Madrid are expanding the mini-narratives into full narratives that could be more suitable for the complete plot of a film, for example. Meanwhile, researchers at the University College in Dublin are trying to teach computers to produce metaphorical insights and ironies by inverting and contrasting stereotypes harvested from the web, while researchers from the University of Cambridge are looking into web mining for ideation purposes. All of this work should lead to better and more complete fictional ideas.

More than a whim

While the fictional ideas generated may be whimsical, WHIM is based on solid science. It is part of the emerging field of computational creativity, a fascinating interdisciplinary discipline located at the intersection of artificial intelligence, cognitive psychology, philosophy, and the arts.

WHIM may have applications in multiple domains. In one initiative there are plans to turn the narratives into video games. Another major initiative involves the computational design of a musical theatre production: the storyline, sets and music. The entire process is being filmed for a documentary.

WHIM could also be applied in areas beyond the arts. For example, it could be used by moderators at scientific conferences to ask probing ‘what-if’ questions to panellists in order to explore different hypotheses or scenarios.

References:http://phys.org/