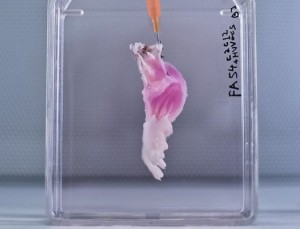

Cornell software identifies bird species from users’ photos

A photo of a Blackburnian warbler, made ready for processing by Merlin Bird Photo ID

While there are already plenty of apps that help birdwatchers identify birds, most of them work by searching a database based on descriptions. Cornell University and the Visipedia research project’s Merlin Bird Photo ID program, however, goes further – it utilizes computer vision tech to identify birds pictured in user-supplied photos.

Users start by uploading a photo that they snapped of the bird in question, drawing a box around the animal to help the software find it, and then clicking on its bill, eye and tail to establish its orientation. They also indicate where and when they saw it.

Merlin Bird Photo ID then uses its artificial intelligence to compare data points in the photo with those from tens of thousands of photos of known species of birds – its database currently includes 400 species that are commonly seen in the US and Canada. It also takes into account the time of year and geographical location at which the photo was taken.

Within a few seconds, the software subsequently presents the user with a short list of the closest matches, including photos and song recordings.

“Computers can process images much more efficiently than humans,” says Cornell’s Prof. Serge Belongie. “They can organize, index, and match vast constellations of visual information such as the colors of the feathers and shapes of the bill.”

The program currently manages to include the correct species within the top three results about 90 percent of the time, although its accuracy should improve with increased use. That’s because it utilizes machine learning, so it builds upon the knowledge it gains each time it processes a new photo.

Plans call for the technology to be added to the existing free Merlin Bird ID app, once it’s able to reliably identify birds in photos taken with smartphones. In the meantime, you can try it out at the project website.

References:http://www.gizmag.com/